Truth Social, Authentication, and Identity

The biggest opportunity for Truth Social - Trump's new platform - is one least well understood: authentication and reputation. It can sweep the table of bots and PSYOP warriors from social media

Follow me on Telegram: @CognitiveCarbonPublic

Truth Social, Trump’s new social media platform that is expected to debut in March, has a unique opportunity to position itself as the ‘trust’ nexus for all existing and future social media platforms, in a surprising but overlooked way—and at the same time deal a death blow to most bots, trolls, and PSYOPs on social media.

In fact, of all the body blows Trump could hit the Deep State with, this one is the most damaging—because it can potentially take two critical tools out of the toolboxes of the world’s PSYOP warriors, those who anonymously wage unseen memetic warfare via social media.

These two tools involve impersonation (theft of voice) and abuse of anonymity (but probably not in the way you might think about that word. There is a thing called “authenticated anonymity” versus “unauthenticated anonymity”. Keep reading.)

I’ll try to explain how all of this could work for Truth Social in this post. If you make it through this post, you’ll know more than 99% of your peers do about how the Internet works with regard to identity and authentication, and you’ll have a good idea how things ought to be structured in the future.

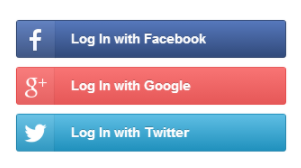

To grasp some of the core ideas behind this post, I have to start with some basics: explaining the difference between “authentication” and “identification”. These are crucially distinct concepts. At the end, as a bonus you’ll understand why login options like the ones you see below are so prevalent these days, and this understanding will lead to the “big idea” for Truth Social.

Let me begin by saying that I am a strong proponent of the right to anonymity—both online and off. There are times when it is in society’s best interest that people be able to speak (and transact) anonymously. This includes transacting (and therefore “speaking”) with cryptocurrency, even though anonymity in this realm also means that the bad guys could potentially use crypto in ways that are illegal.

They will find a way to transact illegally anyway, they always have. That’s the nature of bad guys; the word “illegal” is a concept the bad guys don’t care about. Building systems that limit the Good Guy’s freedoms without affecting the behavior of the Bad Guys is simply bad policy. This same issue comes into play with trying to bluntly censor “hate speech” on the Internet.

Speaking anonymously via cryptocurrency transactions might include, for example, donating funds to the Great Canadian Trucker Convoy of 2022—people who are definitely Good Guys (TM) deserving of support—but allowing you to donate in a way that can’t be interfered with by leftist ideological opponents who control platforms like GoFu*#Me (misspelling deliberate.)

Anyhow, the idea of maintaining anonymity in cryptocurrency realms is a controversial position, I acknowledge that. You are free to form your own opinions.

Whatever your opinion is of the colorful and now deceased John Mcafee, he was a brilliant man, and he understood and expressed the power that regular people can and should possess — through cryptocurrency done correctly— when it comes to their personal financial expressions, and synonymously, their freedom of speech.

The speech he gave in Barcelona in late 2019 (below) is probably why, nine months after his “death” by “suicide” in a Barcelona prison, his body is still on ice in the morgue there. (His lawyer says he’s never seen anything like this in the past. Many things about this case are fishy as all hell.)

That said, yes: there are problems that arise when this right of anonymity (note that I use the word ‘right’ here, and not ‘privilege’ — again a crucial distinction) is abused for speech, whether that speech is conducted online or not; we’ve all dealt with the nastiness that can occur online when people, hiding behind anonymous accounts, say nasty and hateful and inciteful things to other people online—things that they would never be caught dead saying face to face to someone who knows their name.

More often than not, however, these “people” are actually paid trolls and agents’ provocateur whose entire purpose is to disrupt inquiry, undermine community building, demoralize opponents, weaken coherence in online discussions, and also inject propaganda and countering narratives.

There is an answer to dealing with this weakness that need not involve censorship, but rather “reputation” based filtering; we’ll get to it by the end of this post.

Let’s start with defining “identification”, as this is the most straightforward of the two key words we’re focusing on here. In a generic sense, “identification” is any process that is used to “prove” that you are who you say you are: your name, address, photo, signature, biometrics etc. typically as captured on some state-issued document like a passport, birth certificate, or driver’s license is used as “proof.”

Although we tend not to think of it at this level of granularity, “identification” basically means that you, by possessing these official documents containing your name, photo, signature and possibly biometric information, can assert: “I, the holder of these officially-blessed documents, am also the person named on these documents, and the State, by issuing these formal documents to me, confirms my claim.”

It is implicit, here, that people seeking to verify your identity in this way trust the issuer (the State.) It is also implicit, but overlooked, that somehow the burden of proof always seems to be on YOU to prove your identity, isn’t that odd… but that’s a rabbit hole for some other future post.

By the way, names are important things; there are a host of religious and philosophical treatises which argue that to name a thing (or a person) is to bring that thing into existence from the chaotic void in the first place (“In the beginning, there was the word.”) But that, too, is a topic for a whole other series of posts…

For the purposes of this post, we’ll use the familiar shorthand that “identity” is your name, address, phone number, resume, photo, etc. that properly establishes “who you are in real life.”

Now let’s dive into authentication. When you “log in” to some page or platform on the web, you are engaging in the process of “authentication”. The website might, or might not, have stored in its database your actual “name” or “identity”, but it does at least require you to know two basic things: your username (a “pseudonym”) and a password (a “shared secret”.)

If you type in both your pseudonym and that shared secret into boxes on the web page you’re trying to access, the server at the other end can check to see if that pairing matches what it expects, and if it does, you are “authenticated”. You are granted access to use that platform. Unless the website goes beyond that and requires you to upload your driver’s license or passport, there is no way to know the name — the real-world identity — of the person who is signing in.

Of course, these days most websites also send you a numeric code via SMS to your cell phone to complete your password setting or changing operation, which essentially exposes your identity to them…but that, too, is yet another topic for another day.

Anyway, herein lies the biggest vulnerability in modern social media: Impersonation. Anyone can set up a username/password for some web service and put whatever name and photo they want to on the account, regardless of whether it matches their real-world identity, or not. They can also use services that give them anonymous phone numbers to receive and send SMS texts from.

From the perspective of other users of the service (let’s use Twitter as an example) how can other users know with any kind of certainty that the account claiming to be “Julian Assange” on Twitter is actually owned and used by the real “Julian Assange”?

It is crucially important for members of a healthy society to be able listen to and thereby form opinions about people, accrued across long periods of time, to understand their perspectives and positions; when this natural process is intentionally disrupted, it creates conditions for grave societal ills.

More subtly: how can we know, for example, that the Twitter account that was once actually used by Julian Assange, still belongs to him and was not stolen by someone else, sometime later? (For those who don’t know: there was an odd series of events that made it appear that “Julian” on Twitter was no longer “Julian” a few months just before his arrest.)

The short answer: there is no way to know. The bad actors who run PSYOP warfare on social media using bots and troll accounts exploit this fact to their advantage. This is sometimes called “theft of voice”, because the people who are claiming to be someone that they are not have “stolen the voice” of the real person.

They can fool people into thinking the real-world person has a point of view, belief system, or ideology that they do not actually have. The bad actors can subtly shift your perception of what is “true”, who is who, and what the person you think you are following (apparently) believes.

To counteract this, Twitter introduced the idea of “blue checks”, which means that Twitter staff have taken upon themselves to go through some extra steps behind the scenes to somehow “verify” that the person who owns that named Twitter account is, in fact, that self-same real-world person. Curiously, the vast majority of “blue checks” on Twitter all seem to be members of the same ideological persuasion. But I digress…

By doing this, Twitter is essentially taking the place of the State in formally establishing identity. There is clearly a trust issue here: do you really believe Twitter intends to always do this correctly—free of coercion and corruption? What is their incentive to be ‘trustworthy’ in this regard, versus what are their incentives to ‘cheat’? What are the consequences for them doing this ‘verification’ in a corrupt fashion? (answer: none.) Who might pay them in order to allow certain agents to conduct psychological warfare on Twitter?

And why is it, by the way, that only ‘special’ people can get ‘blue checks’ on Twitter and most ‘normal people’ cannot? Don’t they collect and use, for SMS verification, every account holder’s cell phone number? Why can’t they therefore “verify” everyone? Why does Twitter hold the ‘power’ of deciding who is “made authentic” —and therefore, “credible” —and who is not? But you know the answer to that one….

This is an important thing to think through carefully. Remember, that to name a thing — or to “verify” or “fact check” a thing — is power. This will come back into view later.

The power of deciding which online accounts are “authentically” valid actually belongs somewhere else; in theory, it belongs to the owner, in combination with some third party “trust network” that everyone else can agree is worthy of placing confidence in. And that third party is probably NOT the State, or Facebook, or Twitter, etc.

Ideally, it is “we, the people”, somehow, and neither any state nor any particular corporation who should hold this power.

Let’s pause this line of thinking for a moment and go back to talk about those sign-in buttons from Facebook, Twitter, Google etc. that we now see on lots of web services. What is that really about, and how does it work?

The idea, introduced many years ago, is called “Open Authentication” or “OAUTH”. From the point of view of users, it offers what appears to be a convenience: instead of juggling 50 or 100 different usernames and passwords for all the various websites you frequent, you can remember just one or two, and use those to “authenticate” (sign in) to everything else. You can “sign into”, for example, foobar.shopping.com using your “Facebook” username and password—even without having to fill in any boxes on the foobar website.

How does that work? It relies on the fact that you are most likely already “signed in” somewhere else to Facebook, Google Gmail, Microsoft Outlook, Twitter, I-tunes, or some other such service, and your computer or phone already has a “cookie” (or token) from those guys “proving that you signed in.”

By offering that “authentication token” to foobar.shopping.com, the web server at foobar can say “well, I trust that if Facebook signed you in and checked your password, that’s good enough for me; I’ll just take their word for it, and I’ll accept their authentication token that they gave you in place of having to generate one of my own.”

This “Open Authentication” system, on the surface, seems to provide some convenience to both you, the user, and the web service provider (foobar.shopping.com) that is using it. The advantage to foobar is that they don’t have to mess with issuing, keeping track of, and validating username and passwords—and offering methods for users to set and reset passwords, which happens all the time and is a major headache. They can instead shift responsibility for those housekeeping chores onto Facebook, etc.

From the point of view of the user, it seems convenient that you don’t have to remember 50 or 100 different usernames and passwords (but a warning: you really should use a unique password for each website if you are truly concerned about data privacy.)

You can narrow down your unique passwords to a small handful (Facebook, Twitter, Google, Apple, Microsoft: the “Big 5”.) Doing this, by the way, makes your digital persona that much easier to “hack”—whether by criminals in the private sector, or by criminals in the intelligence community. Fewer passwords need to be cracked to “hack all of you”.

You might have noticed, by the way, that the “Big 5” don’t seem to offer you the same convenience amongst themselves: that is, they tend to not to let you sign into their own properties using the OAUTH system of their competitors (signing into your Google account with your Microsoft login, etc.)

That is interesting, and now you’ll learn why that is.

First of all, anytime you visit any web page that has a “like and share” icon or a login button from the “Big 5”, that web page (foobar.shopping.com, for instance) will “talk” to a server at Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, which gets asked to provide that button image and the code behind it to display and use on foobar.shopping.com’s page.

Straight away, that means that simply visiting a page that has these icons or login buttons on them already reveals to the “Big 5 boys” that you have visited the site foobar.shopping.com. This information isn’t revealed to just one of them; it is revealed to all of them whose buttons appear on foobar.shopping.com (and for that matter, to every advertising provider whose ads show up on the page you’re visiting.)

Even though you didn’t even login yet, the “Big 5” already know at least the IP address and time/date of the visit to that third party website—simply because your browser, while visiting foobar.shopping.com downloaded their login buttons and icons.

If you *also* happened to be logged into Facebook, etc. then “tracking cookies” likely will have been sent, too: and now Facebook etc. can learn (indirectly, via your IP address and those cookies) what other sites you visited, when, and how often.

If you take the further step of actually using the OAUTH button to sign into foobar.shopping.com with one of your “Big 5” accounts, which they make awfully convenient for you to do, now they really have some rich data about you to add to their database.

Now they have your full identity, at least whatever you’ve given to the Big 5 when you created your account with them. Again, and this is crucial: by signing in this way, you are revealing to the “Big 5” when and where (your IP address reveals your location) and how often you visited foobar.shopping.com.

Just think of what that is worth to them. And also, to the intelligence agencies that are secretly in bed with them…

Facebook made a “power move” years ago by being one of the first of the Big 5 to offer Open Authentication services to non-Facebook websites (sign in with Facebook.)

One of the biggest things that happened “under the hood” on social media platforms in the last decade, therefore, is one thing that most people know little to nothing about and pay zero attention to: how the “Open Authentication” system gives very valuable information away to the “Big 5” simply by being offered, and even more valuable information if actually used. A key point to make here is that it was the offering of this capability that was one of the reasons Facebook’s user count grew so rapidly. It is a tempting convenience for both users and third party websites, and Facebook and Google and Microsoft took advantage of this.

Now let’s cover one more topic—the idea of using digital signatures to secure information on the web (and to prove ownership of digital content)—and then we’ll tie everything together.

Very shortly after the “Internet” came to life in the early 90’s, it became necessary to limit access to certain functions of websites only to those people who should be granted permission. Permissions might include the ability to read the information housed on the website (in the case that it was housing “private” information or data), but certainly the ability to WRITE information hosted on the website, including accessing and changing private information pertaining to accounts (names, email addresses, passwords, etc.)

In the early days of the web there were many reports of hackers “defacing” websites owned by others, which resulted from hackers cracking or stealing passwords and taking over the ability to edit the text, links and images on those sites.

Someone figured out how to do “password protection” in those early days just after the birth of the web to try to lock things down, and about five minutes later, someone else figured out how to “hack” that initially simple-minded password protection, and the race was on.

Methods to protect and secure websites grew in sophistication rapidly, as did methods to compromise them. New lockpick tools always come along right after the latest padlocks get produced by manufacturers, and the same is true online. The race is perpetual, and the lawmaker/lawbreaker dynamic has been with humans since civilization began.

One of the innovations for securing web content that has been successful and has persisted came about in the early days, and it has to do with what is called “Public Key Cryptography”, which requires “Public Key Infrastructure” for which we’ll use the acronym PKI.

This bit of mathematical magic is the basis for the “SSL” system that makes https:// pages work; it is PKI that in theory protects your private information and credit card numbers from (casual) hackers.

We’re not going to go into any depth about how PKI works here, nor will I attempt to explain why I used the word “casual” in the previous sentence; there are plenty of videos you can find on the web that explain PKI. Think of PKI as simply “the tools and systems needed to make Public Key Cryptography work on the web.”

We will at least explain that Public Key Cryptography involves the use of a Private Key (a “password” that only you possess, one that stays on your devices only) and a Public Key (a separate “password” used only for verification, freely publishable anywhere, and needed by anyone who wishes to validate you) that can be shared to the world.

The basic idea is that you can use your Private Key to “scramble” some key information that you want to keep safe—or in other words, digitally sign—and then you can share that scrambled information along with the Public Key so that others can unscramble it and read it (or verify the “signature”.)

However, even though other people have your Public Key (it’s called Public for a reason), which allows them to unscramble your secret message to verify that you created it, they cannot use it themselves to scramble information that could later be unscramble or verified with your Public Key; only you can create the scramble, and only with your Private Key. This means that the bad guys cannot pretend to be you; they cannot impersonate you or steal your voice, because only you can sign things with your Private Key.

In this way, you can build systems for the Internet that can prove you are the owner of certain digital content (not limited to just passwords), because you can “sign it” with your Private Key, and others can verify that it belongs to or was created by you by checking the “signature” using your Public Key.

Put another way, you can authenticate digital content that you create—prove that it genuine—by signing it using a Private Key, and others can then prove to themselves that it belongs to or was created by you by validating that signature, all through open-source PKI tools.

It turns out that the same PKI machinery that is used to provide HTTPS:// pages and to manage usernames and passwords for logging into websites these days can also (by and large) already support the concept of “digital signatures” which offer a way to prove authenticity or ownership of certain digital content.

So here is the final idea, and then we’re on the home stretch to understanding the role that Truth Social could come to play in the future.

Supposed that you like the handle “CognitiveCarbon” and you want to use it on any number of social media platforms as your chosen persona. How can other people be certain that the “CognitiveCarbon” on substack is the same person who writes as “CognitiveCarbon” on Telegram, or Gab, or Parler, or Twitter, etc? How can you determine which are the ‘genuine’ ones and which are fakes?

Well, one thing that each of us can already do (but it’s too complicated technically for the vast majority of people) is to use a tool called GPG (Gnu Privacy Guard) which is simply an open-source software package that lets you manually create and use Public and Private keypairs for digitally signing or encrypting content (encrypting means scrambling the data in some document that you want to remain private so others can’t read it.)

If you were capable and motivated, you could create a keypair using GPG and use it to digitally sign, for instance, a set of images; and then you could upload those signed images to each of your various social media accounts.

If your followers also had GPG, and knew what to do, they could in principle download the image from your posts and run a digital signature check with GPG to see if it corresponds with your Public Key (how they get that key to use is an issue we’ll get to, but let’s say for now that you provided a download link to your Public Key in some prior post on all of your various social media platforms.)

This is a bit complicated to follow, but the basic idea here is that you can “digitally sign” some content, upload it to social media, and followers can “verify” that digital signature if they have access to your Public Key. They can assure themselves in this way that “you” are “you” on various platforms, because only you could have signed the content with the same signature.

What this provides is a way — even if you are anonymous! — of letting people prove to themselves that at least it is the same person who is creating your content on Twitter over a long period of time (because the signature doesn’t change over time), and further, that this same person is also behind this or that account on Gab, Telegram, etc. (because the same signature can be used to verify images uploaded on those platforms.)

Put simply: digitally signing content it is a way to “preserve voice”—to defeat impersonation. Provided that you keep your Private Key safe, nobody can “impersonate” you on these other platforms, because they wouldn’t be able to create proper “digital signatures” on your content.

Another key point to make is that doing something like this lets you establish authenticity - asserting to followers that the post contains genuine content of yours - independent of whether the platform directly supports that feature, or not.

So here is where the interesting bit comes in: if there were some system to warehouse everyone’s Public Keys (a centralized directory of sorts) and if there were dirt-simple online tools that automagically let you “sign” content that you post to a variety of social media, then a provider like Truth Social could offer a unique feature like this: “in my feed, please filter out and never show any content or comments or replies from people who do NOT digitally sign their content” (because in that case, they are likely bots or trolls.) Truth Social doesn’t need to prevent them from creating content; they can do so all they want. But if they won’t sign it, you can choose not to see it.

Truth Social could then take things one step further: they could allow your Public Key (warehoused on some central server of theirs) to be “signed” by other people you know and trust to add credibility and vouch for you. Let’s say I want to be anonymous as “Mark Twain” on social media, but my friends, who know me as “Samuel Clemens” in real life are willing to “sign” my “Mark Twain” Public Key because they know and trust me.

Then, even though others don’t know who “Samuel Clemens” is in real life, they can see any number of trusted people that they do know who vouch for him: because they have “signed” his Public Key with their own. Their signatures say “this is a good guy”. This is the idea behind the “web of trust” that actually powers all of SSL, just so you know.

So now we get to the key idea: Truth Social should position itself as this “central clearinghouse” of Public Keys and provide trivially easy to use tools to (1) create, manage and vouch for Public Keys; (2) sign content that can be posted to other social media and (3) validate signatures on signed content with a simple click. While these underlying pieces already exist in some form, they are too hard for most people to use. It needs to be one-click simple.

With just that functionality, coupled with the ability to automatically filter out any unsigned content, the quantity and reach of fake PSYOP bot and troll accounts would be virtually eliminated.

Do you know what other systems uses digital signatures of each piece of content to verify whether or not it’s trustworthy? Your Windows 10 operating system: all of the important systems programs in the C:\Windows directory are digitally signed to prove they are genuine and unaltered. That’s how anti-virus software helps protect your system. We need a similar system to help us eliminate the mind viruses that contaminate our social media platforms.

Truth Social does NOT need to position itself to be the “cop” in order to be the newest ‘nexus of trust’ for validating digital identity and authentication with regard to Public Key signatures; it doesn’t have to be (but it could be!) the “trust authority” in charge of verifying identity (the Twitter “Blue Check” idea.) We don’t need to trust yet another corporation to act in place of the State, or to displace the “Big 5”.

Truth Social simply need to create tools and provide methods, using their platform, open-source tools, and easy-to-use APIs to give the people the power to take back for themselves the management of these crucially important functions (authentication, identification, building networks of trust, and ownership tagging via digital signatures.)

If Truth Social allows people to digitally sign content created and posted on their own platforms, validate signatures on content, and supports the ability to filter out unsigned content…the world changes for the better.

If Truth Social simply offered the tools to power all of this…to seize the initiative, as Facebook did with OAUTH — then it could also keep track of who was requesting and using Public Keys from its warehouse for checking posted content elsewhere. That gives Truth Social the ability — if it chose — to crack down on PSYOP warriors on all platforms, in ways that would all but eliminate them. It doesn’t require giving up anonymity; but it does offer a means to automatically filter out people who won’t sign their own work.

A final step involves creating a ‘reputation’ system tied to all of this. If you are a content creator, even an anonymous one, and you have a collection of “vouched for” signatures on your Public Key to show you have a network of support, you might also earn, over time, a certain “reputation” rating to help boost your credibility and therefore the visibility and positioning of your content in a feed.

A website that already does this well is StackExchange.com. What that system allows them to do is implement something that works like this: “if you are a brand new user, welcome! You can read posts here — but you cannot create any of your own, or reply for a few weeks. Once you’ve been here a while, you can start to post your own content, but you still cannot reply to others. Once you’ve posted a bit and other people have rated and ranked your posts, you can begin to reply. But if people downvote your replies often enough, you’ll lose the privilege to reply.”

Imagine how that feature, combined with the option that you “sign your own work” with a digital signature, could all be eliminate the bad actors on social media—all while preserving anonymity.

In a subsequent post, I’ll talk about the importance of a new global infrastructure for networks (something like SpaceX’s Starlink) that is also required to make a new social media platform successful over the long term.

This sounds like an awesome system. I wonder if Truth Social has even given any thought to all this. I've pretty much left FB & Twitter and the others behind, in favor of Substack, because I am so sick and tired of reading obvious troll/bot comments.

This is an excellent article. It outlines the potential for the TS to embrace the technology (already in place) to remedy the pervasiveness of fake news & social manipulation through disinformation - GREAT JOB, CC! On paper, the undertaking - through the established repository - appears trivial. The problem is: will the TS take on it? If so, where on the roadmap would it be?

Also, I wonder how related to that, if at all, is Elon Musk's tweet about creating a site where the public would "rate the core truth of any article & track the credibility score over time of each journalist, editor & publication", tweeted on 5/23/18…